By Peter Anderson, Director, Mukilteo Historical Society

About 6:00 pm on September 17, 1930, Mukilteo’s normal tranquility was shattered by two huge blasts. Besides upsetting the normal tranquility, windows in Mukilteo and Everett were shattered, chimneys were cracked and foundations were damaged. It didn’t take long before residents realized that the event they had often feared had occurred: the Powder Plant had exploded!

Fortunately most of the plant employees had left for the day, and no one was killed. It could have been much worse had it not been for the heroic efforts of two men who went back to the plant to keep the fire from spreading. Tony Radonich, a nephew of the mill owner, and Risto Luchich dug a ditch around the main building to keep the fire away from where 65 tons of high explosives were stored.

Although there were no fatalities, there were some serious injuries and extensive property damage. Pieces of flying glass cut one woman’s jugular and caused another to lose an eye. Some of the injured were given first aid by Mukilteo’s Doctor Claude Chandler in his office and drug store; some were transferred to Providence Hospital in Everett. Homes near the plant were demolished. Glass storefronts in downtown Everett were shattered. Telephone service in a large area was disrupted. The shock wave from the explosion created a large ebb in the harbor that lifted boats clear out of the water. Many personal recollections of the day the plant blew have been written. When the mill exploded, Lillian Sullivan had a cup of coffee in her hand, which she spilled down her husband’s back. Grace White had just canned peaches, and they were now smashed on the floor along with the oven door.

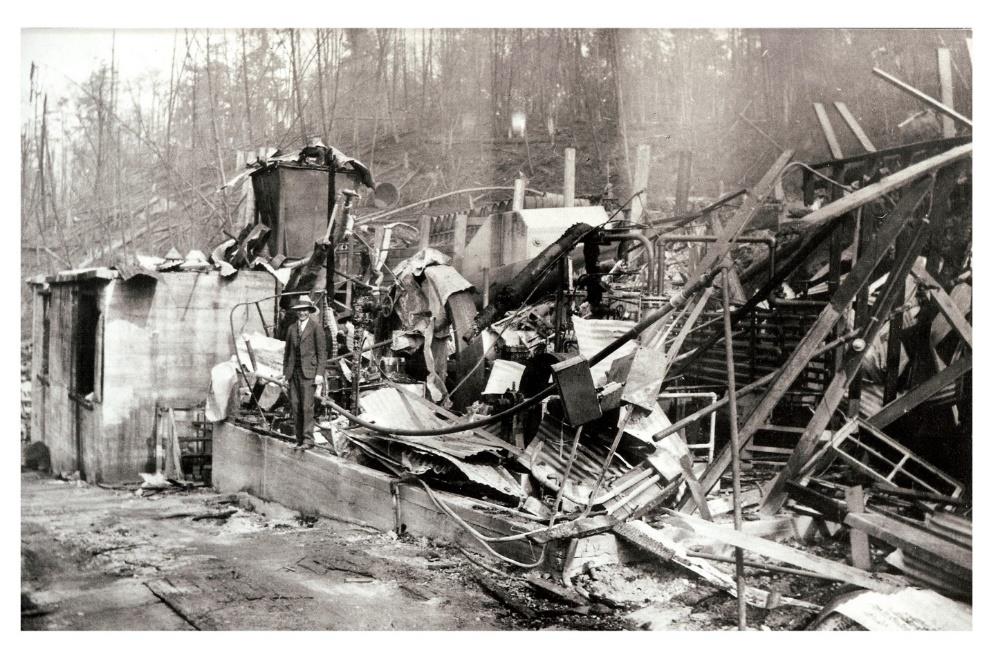

Damage to the plant was estimated at $250,000 and another $250,000 in losses to private homes and businesses. Affected property owners discovered their insurance did not cover losses due to explosions. Many individuals and businesses filed claims for damages against the company that owned the plant.

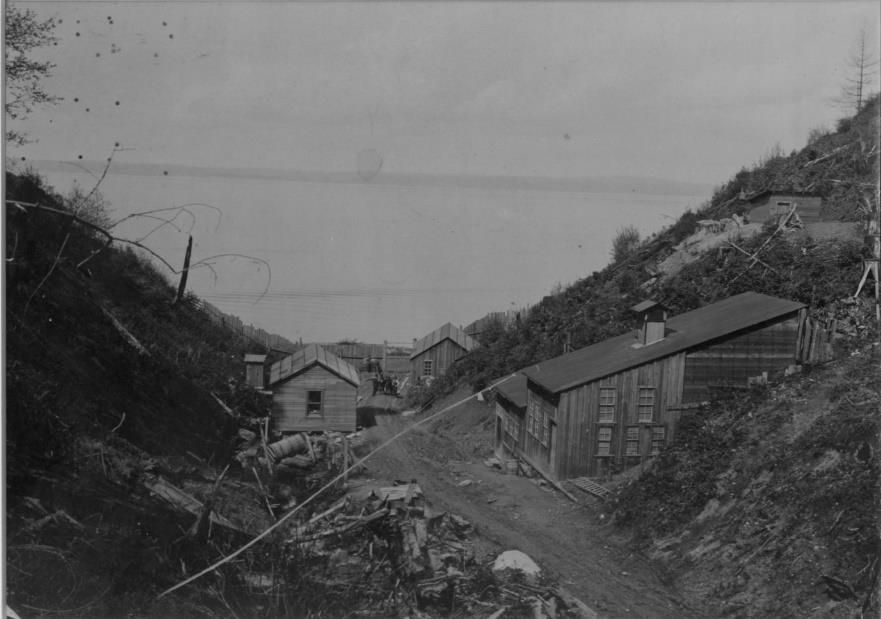

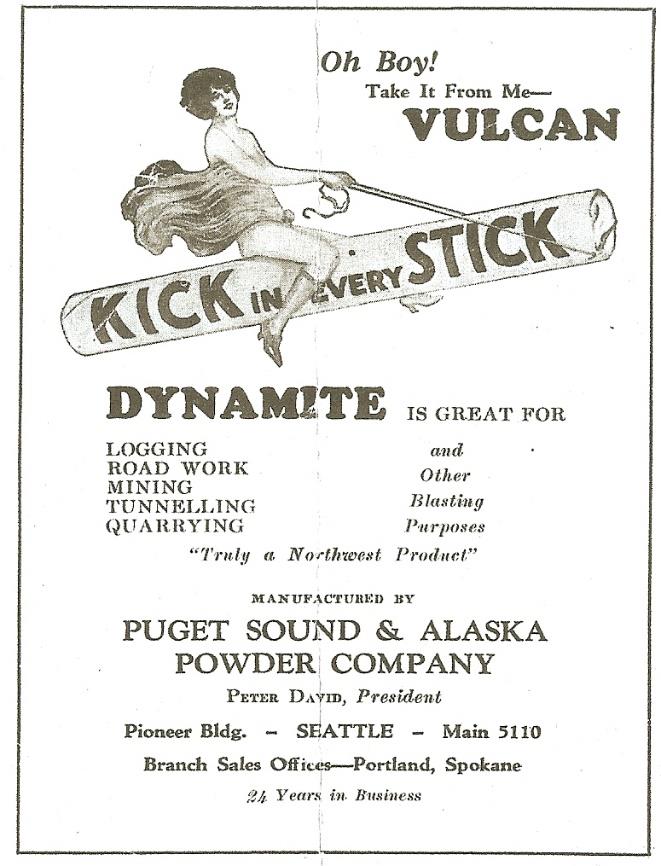

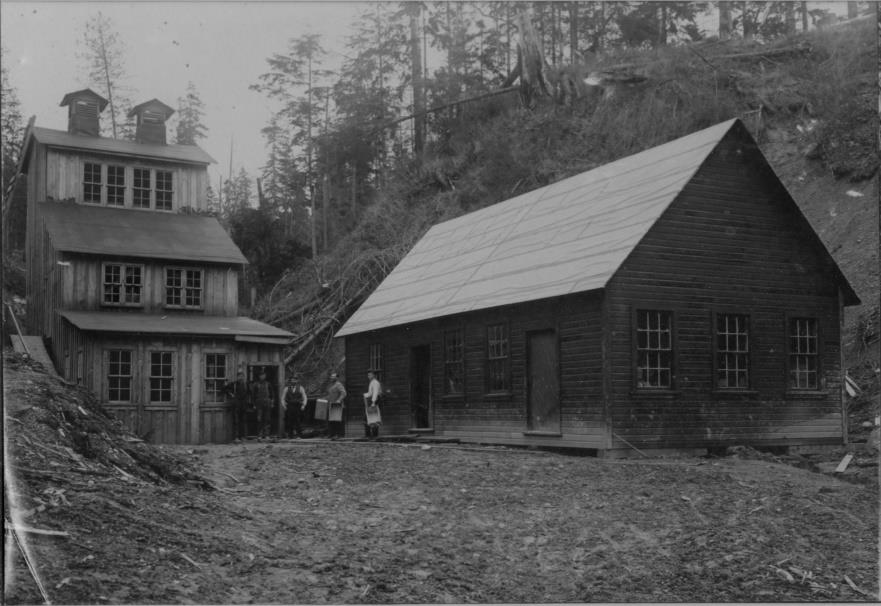

The Puget Sound and Alaska Powder Company was organized around 1906, and established the powder mill located in a gulch near the Everett/Mukilteo border. The plant employed about 30 people and had a monthly capacity of about 400,000 pounds of dynamite that was used for clearing land, logging, mining and railroad work. Advertisements for the company’s trademark Vulcan dynamite featured the slogan “Kick in Every Stick”.

A theory emerged in the aftermath of the event as to the cause of the fire and subsequent explosions. Clarence Newman, a worker at the powder mill mixing shed, was given the job of recycling “dud” dynamite sticks that had been returned to the company because they had failed to explode. As a cost cutting measure, the company had cut down on the nitro content and substituted ammonia powder. This led to a less effective explosive mixture used in the dynamite sticks and hence more duds. The initial safety recycling procedure called for another employee to sweep the spilled mixture from the failed sticks into a sack and carry it down to the shore of Puget Sound where it could be safely burned.

There came a time when the company changed the recycling procedure to further economize their operations. Instead of wasting the spilled explosive, Clarence was instructed to recycle it also. Apparently, the company was oblivious to the fact that, when the ammonia powder soaked up moisture from the floor, it would become extremely volatile. On the fateful evening of September 17, 1930, spontaneous combustion caused the explosive mixture to flare up. There was no fire extinguisher in the building, and no hose outside. While Clarence dashed from the mill to spread the warning, flames raced to the ammonia-impregnated wooden walls of the mixing shed.

The first blast occurred when 9,000 gallons of nitroglycerin ignited, hurling a fireball into the sky. Witnesses first reported seeing dark smoke coming from the plant, and then, after the blast, a yellow/gray mushroom-shaped cloud formed that could be seen for miles. The second blast that occurred shortly after the first was most likely due to 100 cases of stump-blasting

powder exploding. The road between Everett and Mukilteo soon became jammed with vehicles, pedestrians and fire apparatus. Some were fleeing the scene in fear of more explosions and some were curious onlookers trying to see what had happened. Police could barely manage to keep the road open enough for fire engines to pass as drivers abandoned their cars or careened out of control into ditches or up embankments on the sides of the road.

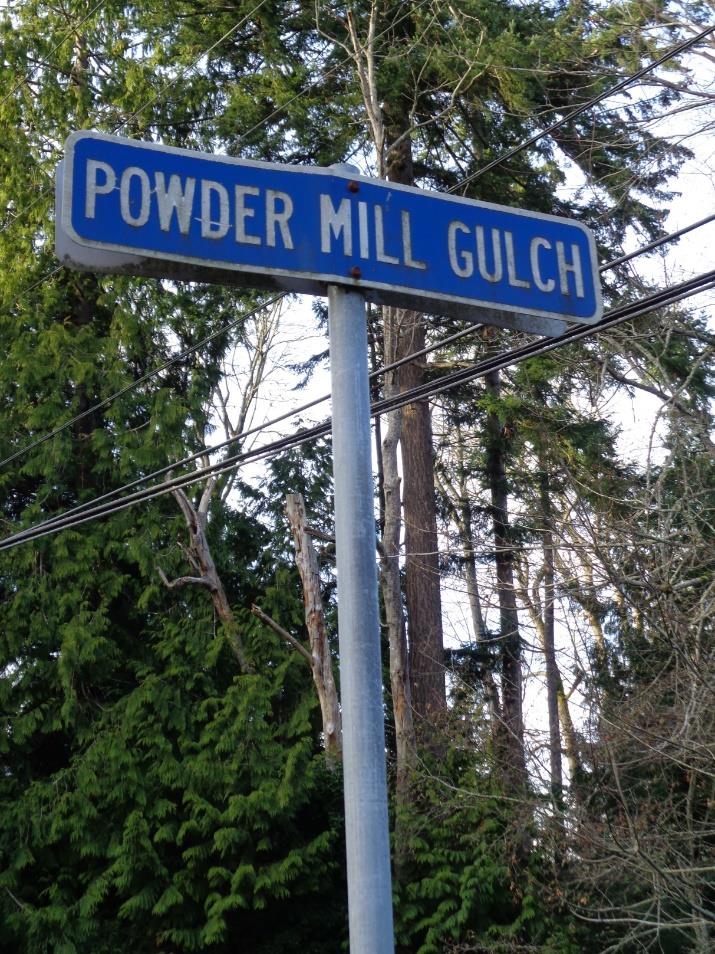

Puget Sound and Alaska Powder Company president, Peter David, vowed to rebuild the plant at Powder Mill Gulch. However residents in the area strongly objected and the plant was never rebuilt. There have been various proposals to develop the site, but it has remained relatively untouched. There does not appear to be any visible remnants of the mill ruins, and, after more than 88 years, the area has become overgrown with brush and trees. Perhaps the only visible reminder of the site location is the blue street sign about seven tenths of a mile into Everett on Mukilteo Boulevard opposite Seabreeze Way.

Lower Powder Mill Gulch, where the powder plant was located, extends northward from the sign on Mukilteo Boulevard down relatively steep terrain to the water. The property has been subdivided into single family residential lots on either side of Powder Mill Creek. The rear of the parcels extends down into the lower gulch, and the front of the parcels faces either Baker Drive or Gardner Avenue.

In recent years, the City of Everett Parks & Community Services Department proposed a Powder Mill Gulch Trail System in the upper gulch area that extends southward from Mukilteo Boulevard to Seaway Boulevard. There is an existing path here that runs along the creek through about 55 acres of City-owned undeveloped land. The trail was not completed all the way to Mukilteo Boulevard due to the lack of a parking area at that end.

Originally published in the 1/2/2019 issue of the Mukilteo Beacon.