By Peter Anderson, Director, Mukilteo Historical Society

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of National Prohibition as stipulated in the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment banned the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within the U.S. and its territories. With passage of the Volstead Act, enforcement took effect on January 17, 1920.

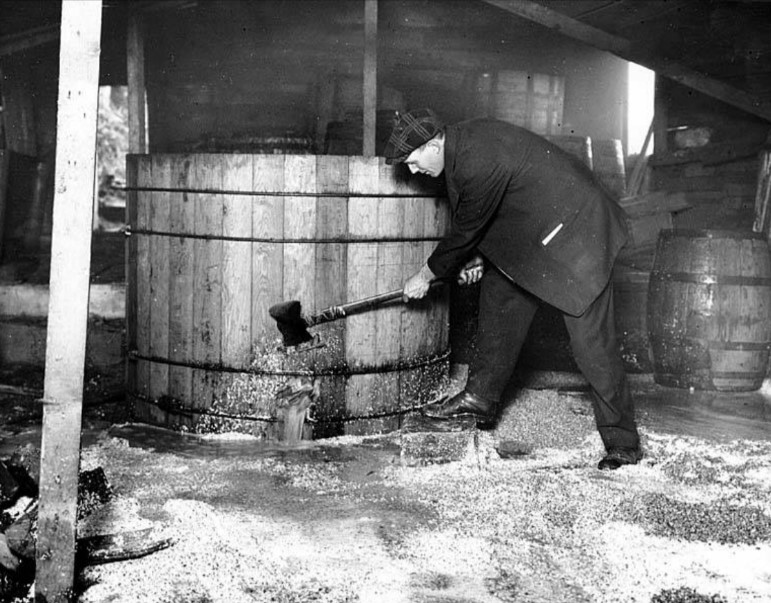

The amendment did not eliminate the craving for alcoholic beverages, so it gave rise to smugglers, rumrunners and bootleggers engaging in various activities to circumvent the law. People in Washington State had a “head start” in these activities because the state had already adopted its own prohibition statute in 1916. Mukilteo and its surroundings were ideal locations for these illegal activities. The area was heavily forested with deep gulches in which to hide stills and stashes of contraband. There were also deep-water coves that could be used to import and export product under the cover of darkness.

People considered the scofflaws as either criminals or local heroes, depending on who you talked to. Enforcement often became a game of “cat and mouse”, and some enforcement officials drifted into illegal activities themselves. It was a lucrative business, and some officials took bribes to look the other way. Perhaps the most notorious local turncoat was Seattle’s Roy Olmstead, a former police officer who became known as “King of the Rumrunners.”

Learning enforcement practices while a police officer, Roy Olmstead thought he knew how to avoid being caught in the lucrative rumrunning business. He left the police force to pursue the business full-time. His operation brought large quantities of Canadian liquor to the Puget Sound area. Olmstead chartered a fleet of vessels and became one of the largest employers in the region, utilizing office workers, bookkeepers, warehousemen, rumrunning crews and legal counsel. At its peak, his organization was grossing about $200,000 a month. Olmstead was eventually caught unloading Canadian whiskey at the Meadowdale dock, just south of Mukilteo.

Another former police officer, C. P. Richards, had a mansion built in an area now part of Mukilteo that became known as Smuggler’s Cove. The building was actually the shell of a manor house constructed in about 1929 to conceal the bootlegging activities going on inside. Some folklore suggests that construction of the manor at Smuggler’s Cove was financed by Al Capone interests, although we have found no evidence that the famous Chicago gangster was ever here personally.

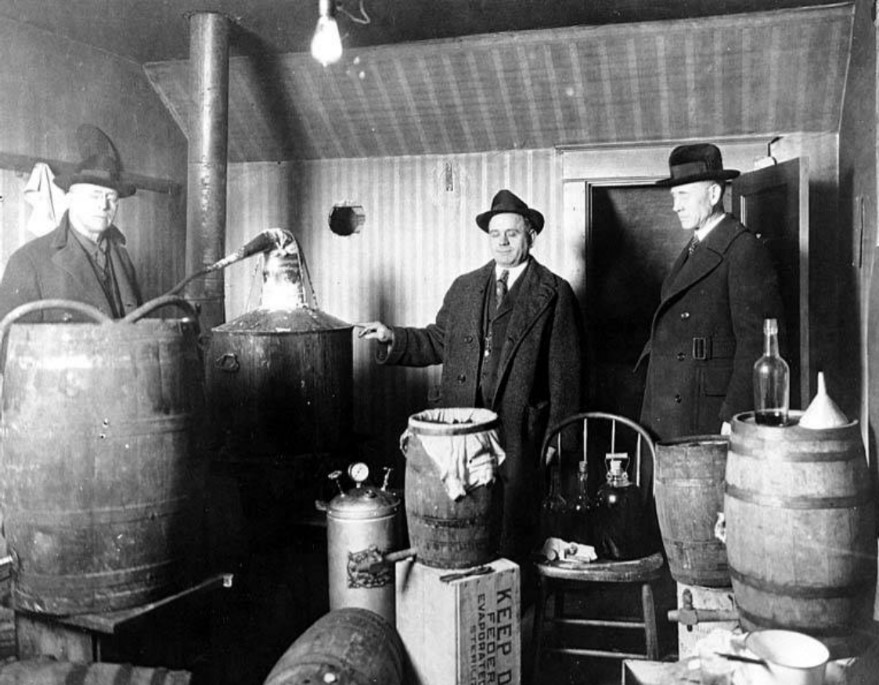

The building had an imposing exterior, but the inside was unfinished. C. P. Richards lived there with only sub-floors and framing. He installed a second basement beneath the first, with a large furnace hiding its entrance. The 9-by-9-foot sub-basement had a still and a tunnel connecting the operation to the gulch and Puget Sound in case the smugglers needed to make a quick getaway.

Use of the fake mansion at Smuggler’s Cove for illegal activities only lasted for a few years. The still blew up after a short period of operation, and enforcement officials raided the place in 1932. After the raid, the sub-basement was cemented over. The following year (1933), the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, which repealed the 18th Amendment, putting an end to National Prohibition.

We have no records of how the Smuggler’s Cove property was owned or used for a period between the end of Prohibition and the end of World War II. Records show after the war, the Axel Jensen family finished the interior of the manor building and made it into a comfortable residence. The three Jensen daughters remember playing games with old whiskey bottles uncovered by their father. Their mother loved the kitchen, which looked out over Smuggler’s Gulch, Possession Sound and the Olympic Mountains. But their father, Axel, was worried that the steep cliff supporting their home could collapse in heavy rains, so he decided to sell.

Dennis and Trudy Tobiason bought the Smuggler’s Cove property in the early 1950s for $18,000. Dennis Tobiason was born April, 1920, in Monticello, Iowa, and grew up on a farm there. After a stint with the U.S. Army, he attended the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he met his wife Gertrude “Trudy” Ortgies. They were married in 1947, and moved to Washington, where they built the Cedardale Motel and Dining Room in Mount Vernon. After four years there, Dennis and Trudy came to Everett, bought and remodeled the old Smuggler’s Cove building to turn it into the Waldheim Restaurant, which they operated for 29 years. They retired from the restaurant business in about 1980, and continued involvement in many community activities, including starting an exchange program between Yokohama, Japan, and many local high schools. Dennis died in Everett on January 29, 2006.

Claude and Janet Faure were the next owners of the Smuggler’s Cove property. Claude was born in Lyon, France on February 11, 1944. His parents owned a patisserie and were forced to cook for occupying German troops. As a young man he was trained in the culinary arts and showed exceptional talent. In 1964, Claude arrived in Edmonds and joined the kitchen at Henri de Navarre. Word quickly spread of Puget Sound’s classically trained French chef. In 1975, he purchased Henri and gave it a new name – Chez Claude. In 1989, Claude and his wife, Janet, opened Charles at Smugglers Cove in Mukilteo, serving the Puget Sound’s finest cuisine in one of its most beautiful settings. The restaurant had an elegant dining room with pink decorations and a spectacular view. Frequent guests included foreign dignitaries, elected officials, and visiting celebrities. Janet continued to operate the restaurant for a short while after Claude’s death in 2014.

County records show that the Claude and Janet Estate sold the Smuggler’s Cove property on November 30, 2015, for $850,000. The buyer was Farland International Development LLC, a general contracting business in Edmonds. The old manor house is still standing on the property. Located in Mukilteo at 8340 53rd Ave W, the 1.7-acre parcel had an assessed valuation of $917,000 in 2019, and all property taxes have been paid through 2019. Checking with the City a few weeks ago did not uncover any upcoming development plans or permit activity at this time. We’ll just have to wait and see what may lie ahead for this storied property.

Originally published in the 3/4/2020 issue of the Mukilteo Beacon.