By Peter Anderson, Director, Mukilteo Historical Society

Authors Note: Portions of this article are taken verbatim from a brochure “The Mukilteo Japanese Memorial” published by the Mukilteo Historical Society.

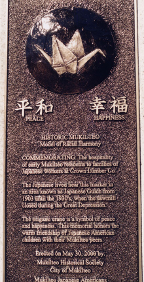

Next month marks the 20th anniversary of the dedication of a monument commemorating the harmonious relationships between early Mukilteo residents and families of Japanese workers at Crown Lumber Company. Located in Centennial Park, 1126 5th Street, the monument was erected on May 30, 2000, by the Mukilteo Historical Society, the City of Mukilteo, and Mukilteo Japanese Americans.

Dedication Ceremony

On June 9, 2000, descendants of original Japanese immigrants joined with present citizens of Mukilteo to dedicate the symbol honoring the town’s historic example of harmonious race relations. They gathered around the monument that supports a bronze origami crane, which symbolizes the historic roots and the continuing goal of peace and harmony among all peoples. Speakers at the ceremony included Mayor Don Doran, Mas Odoi, David Tanabe and Beverly Dudder Ellis. Odoi had been born in a humble three-room house in Mukilteo’s Japanese Gulch.

Seattle sculptor Daryl Smith designed and cast the bronze origami crane and commemorative plaque for the monument. The $10,000 sculpture was paid for by private donations and gifted to the city by the Mukilteo Historical Society. The bronze plaque on the base of the monument includes the words peace and happiness written in English and Japanese. The monument continues to stand as a tribute and memorial to those early Japanese mill workers who came to Mukilteo seeking a better life.

Japanese Mill Workers

In the early 1900s, many Japanese men came to Mukilteo to work for the large lumber mill here. In many parts of the region, competition from these foreign workers was not welcomed by American workers who were moving into the territory from the east. In nearby Everett, for example, some local citizens organized in 1904 and 1907 to drive out Japanese workers from the Clark-Nickerson Mill.

Although there was some initial resistance in Mukilteo, efforts to drive out Japanese workers here failed because of the strength of the Crown Lumber Company which needed these workers. In 1905, our population was estimated at 350, of which 150 were Japanese families who lived in Japanese Gulch and whose breadwinners worked at the lumber mill.

Crown Lumber had one employee called the “book boy” who represented the Japanese employees in all matters related to their work, recruitment, families, and housing. The company considered their Japanese mill workers to be industrious and trustworthy employees who needed very little supervision once they were instructed in their jobs.

Common labor rates for Mukilteo’s mill workers in the early 1900’s were $2.00 to $2.50 per 10-hour workday. The mill operated 6 days a week. In 1918, unions succeeded in obtaining an 8-hour workday and, by 1930, the labor rate had increased to $3.50 per day for 8 hours work.

Mukilteo’s historic Pioneer Cemetery contains grave markers honoring three Japanese employed by Crown Lumber: Tokumatsu Shirai, who was killed when a large log rolled over him in 1908, Goro Wadatani, who died of apoplexy in 1908, and Rikimatsu Okamura, who died in 1913. Although no marker has been found, a baby girl, Kaijo Tamai, died of crib death in 1918 and is also believed buried here.

Life in Japanese Gulch

With support from Crown Lumber, Mukilteo’s Japanese community built a village in a ravine just above the lumber mill. The village comprised a number of unpainted dwellings situated about 600 feet along each side of a plank and dirt road. A creek ran down the ravine from large reservoirs higher up in forested land. Deep pools along the creek’s mile-long course provided fish for consumption. Japanese elders built a large community center for programs, movies, games and other recreations.

Over time, the residents of Mukilteo and Japanese Gulch began to reach out and learn from each other. As they did, their initial prejudices and mutual suspicions began to wane. One important step was the decision by the Japanese to buy their goods locally instead of importing goods from merchants in Seattle. Many of the Japanese quickly recognized the importance of learning English and trying to understand American customs.

During her school years, Clara Kane remembers teaching Japanese people to read, write and converse in English. She met with the men three days a week in the evenings and women and children in the afternoons. The women also wanted help in sewing, cooking and baking American style. Clara continued teaching the Japanese up until Crown Lumber closed in 1930.

The Japanese children were very good students in the Rose Hill School and Everett High School. Realizing they were not taxpayers, the Japanese wanted to make contributions to the Rose Hill School. They paid for one of the utilities, bought the curtain for the stage, and donated two busts – one of Washington and one of Lincoln.

Sad and Difficult Times

Mukilteo’s economy was inextricably connected to its lumber mills, so their closure in 1930 had a devastating impact on the community. The Great Depression forced Crown Lumber to close, and all the Japanese mill workers and their families moved away to find work elsewhere. The thriving village that had been at Japanese Gulch became abandoned.

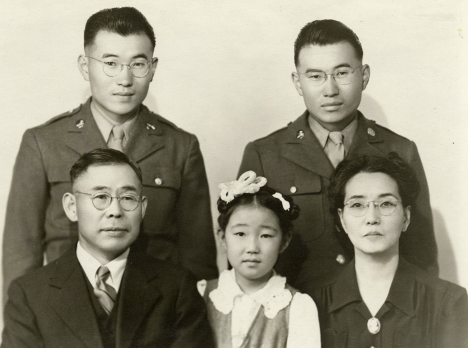

Mukilteo’s Odoi family moved to Nahcotta, in southwestern Washington in 1931. Their twin sons, Mas and Hiroshi Odoi, graduated from Ilwaco High School as co-valedictorians in 1939. Mas was in his third year of study in electrical engineering at the University of Washington when Imperial Japan struck Pearl Harbor.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor led to terrible consequences for Japanese Americans. The U.S. Government immediately labeled them “national security risks” and placed a curfew on all Japanese living on the Pacific coast, regardless of whether they were American citizens or not. Soon thereafter, all persons having Japanese ancestry living on the Pacific coast were evacuated to “relocation centers” enclosed by barbed wire in remote areas of the U.S. They could only bring what they could carry, with just 72 hours to get ready. Everything they owned had to be sold cheaply, given away or stored in warehouses during the war. Most ended up losing everything.

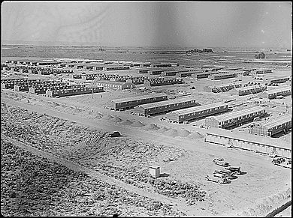

The entire Odoi family, including Mas, who had to give up his UW studies, was forcibly moved first to the Puyallup Assembly Center and then to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho. Minidoka was one of 10 isolated war relocation centers in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. These were built in response to an executive order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942. Some of the camps were still being finished as the detainees arrived.

Minidoka imprisoned people from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. The camp was constructed on Bureau of Reclamation land which was designed to turn the high desert of Idaho into arable farmland. The entire camp extended over 33,000 acres, although only 900 acres were used as residential areas. Minidoka had 36 residential blocks. Each block had 12 barracks, a mess hall, and a latrine. Each barrack was 120’x 20’, which was then divided into six units. Each unit would house a family or a group of individuals. Each unit had a single lightbulb and a coal burning stove. The walls dividing the units did not extend to the ceiling and the barracks had no insulation. There was little to no privacy for anyone. At its peak, Minidoka held 13,000 detainees. It is now a National Historic Site, although few of the original structures remain.

Loyal Americans

Despite their mistreatment during the war years, most Japanese who had lived in Mukilteo’s Japanese Gulch retained good memories of their lives there and became solid citizens. As soon as restrictions were lifted, twin brothers Mas and Hiroshi Odoi volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army. After training in 1944, they both joined the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team and fought in the European Theater.

The 442nd RCT is best known for its history as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who fought in World War II. Beginning in 1944, the regiment fought primarily in the European Theatre, in particular Italy, southern France, and Germany. Many of the soldiers from the continental U.S. had families in internment camps while they fought abroad.

In March 1945, the 442nd RCT was secretly shipped to Italy to breach the Nazi Gothic Line in the Apennine Mountains. During the opening attack in the early morning of April 5, 1945, a mortar exploded behind Mas Odoi, riddling his leg and body with shrapnel. Though painful, they were not as serious as the artery injury on his throat where he could feel a spurting stream of blood. He temporarily lost consciousness, but woke up and staggered to his feet, limping to a tent hospital a few miles to the rear. Mas received a Purple Heart and Bronze Star, and spent the rest of the war in military hospitals recovering from his wounds. At war’s end, he returned to his unit to work with his brother on nominations for medal citations.

The 442nd RCT is the most decorated unit of its size in U.S. military history. The unit earned more than 18,000 awards in less than two years, including 9,486 Purple Hearts and 4,000 Bronze Star Medals. The unit was awarded eight Presidential Unit Citations (five earned in one month). Twenty-one of its members were awarded Medals of Honor. In 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and associated units who served during World War II. In 2012, all surviving members were made chevaliers of the French Légion d’Honneur for their actions contributing to the liberation of France and their heroic rescue of the Lost Battalion.

A high percentage of Japanese-Americans from Mukilteo served in the army during WWII. Besides the Odoi twins, those in the 442nd RCT included Toku Wakabayashi, Yukio and Bob Takeuchi, and Hideo Onada. Those who served in the Pacific Theater included Shigeo “Conk” Takeuchi, Yasuo Onoda and Roy and Isao Hada.

Reparations

Despite the unconditional loyalty and heroism shown by Japanese-Americans during WWII, the nation was slow to recognize and repair the injustices they had endured as part of President Roosevelt’s 1942 Executive Order. There was some opposition to the incarceration, leading to several court cases attempting to overturn the executive order. Despite these efforts, the Executive Order was not overturned until late 1944, with the case of Ex parte Mitsuye Endo in which the Supreme Court ruled the Executive Order unconstitutional. The court’s ruling noted that two-thirds of the population being incarcerated were Japanese Americans who were United States birthright citizens and were stripped of their rights as citizens because of their ethnicity.

Even with the Supreme Court ruling, it would take a long time for reparations and appropriate recognition. In 1983, almost forty years after the war ended, the federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians found that there had been no military necessity for the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans and that a grave injustice had been done. Finally, in 1988, Congress enacted the redress bill, HR 442, that awarded $20,000 to every Japanese-American evacuee, along with a presidential apology. On October 5, 2010, President Barack Obama signed a bill granting the Congressional Gold Medal, collectively to the Japanese-Americans in the 442nd RCT and the Military Intelligence Service for their extraordinary service in WWII.

Return to Mukilteo

After the war, Japanese-American soldiers returned to many different parts of the country. Mas Odoi moved to Chicago and started a TV repair business. There he met and married his wife Frances, and together they had two sons, Gary and Richard. Mas spent many years, first in Chicago and later in Los Angeles before returning to the Puget Sound area around 1990. Here he became an active member of the Mukilteo Historical Society, driving to many meetings and events even in bad weather. He was a popular speaker at various local venues, relating his life experiences after growing up in Japanese Gulch. The University of Washington awarded him an honorary degree as part of its program to recognize Japanese-American students that had been removed from their studies and sent to Relocation Centers in 1942.

Mas Odoi was instrumental in getting the Japanese Memorial built in Centennial Park. He wrote letters as early as June 1989, proposing a memorial and worked tirelessly with the Historical Society for over 10 years to bring his proposal to fruition. The words “Peace and Happiness” that appear on the monument plaque reflect his philosophy of life and fondness for the people of Mukilteo. He was named Mukilteo’s 2008 Pioneer of the Year and participated in that year’s Lighthouse Festival parade and reception.

Mas Odoi died July 28, 2013, and was buried with full military honors at the Tahoma National Cemetery in Kent, WA. His nephew, Steve Odoi is an active member of the Mukilteo Historical Society, continuing the family’s tradition of community support. Steve spends most of his time in Alaska, but is currently visiting Mukilteo, so be sure to say hello if you see him. The monument in Centennial Park stands as a reminder of the contributions made by Japanese immigrants and their descendants to the community spirit we share today in Mukilteo.

Originally published in the 5/27/2018 issue of the Mukilteo Beacon.