By Peter Anderson, Director, Mukilteo Historical Society

When the first permanent settlers arrived in Mukilteo, they were surrounded by an abundant supply of timber that could be used for building materials. Plenty of tall Douglas fir could be cut and formed into lumber used for joinery, veneer, flooring and construction. Tall native cedar trees were abundantly available for making roof shingles and exterior siding. There was more than enough of these forest products to satisfy local building needs, so logging camps were soon established to harvest timber for export to other regions.

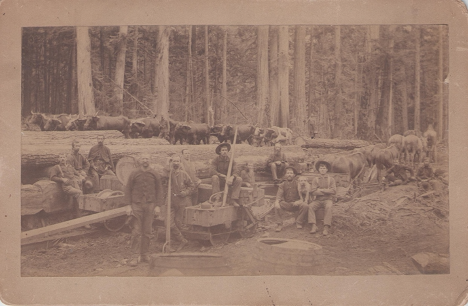

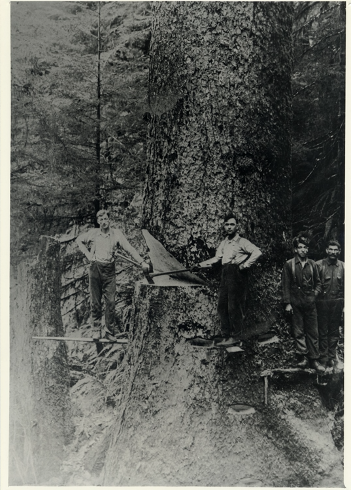

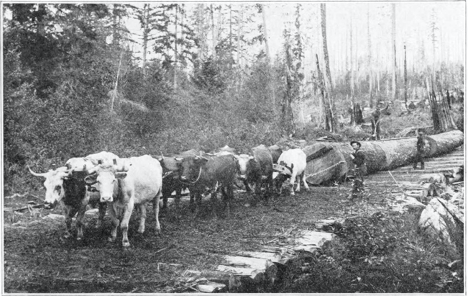

Trees were cut by hand and, early on, pulled by oxen along rudimentary skid roads from the logging camps to the water where the logs could be floated to sawmills. Logging crews used peeled logs to fashion primitive rails or skids to make it easier for the oxen or horses to pull heavy timber. Workers would walk ahead of the animals to apply oil on the skids, giving rise to the expression “greasing the skids.”

In 1881, John Dolbeer invented the donkey engine that revolutionized logging. It replaced animal power, which was slow and could not negotiate steep terrain. The donkey engine consisted of a single-cylinder steam engine connected to a horizontal capstan mounted on several log skids. By wrapping cables around the capstan, the engine could pull huge loads that would otherwise have required animal power. The first donkey models pulled the logs toward the engine. When it was time to move to a new area, the cables were attached to a tree, stump or other strong anchor, and the engine would drag itself to the next logging site.

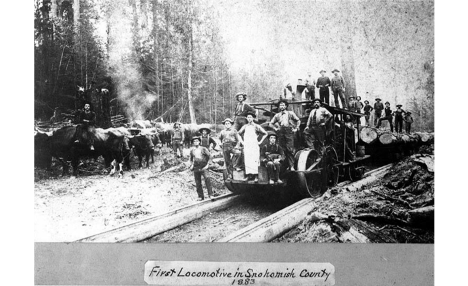

As logging operations moved farther inland, logging railroads were built for transporting the cut timber to waiting ships or coastal sawmills. These early railroads used grooved wooden rails that had been patented by Blackman Brothers. In 1883, Blackman Brothers boasted having the first “locomotive” in Snohomish County near Mukilteo and Marysville.

Sawmills were established to cut logs into finished lumber. The Mukilteo Lumber Company, established in 1903, was purchased by the Crown Lumber Company in 1909. The $800,000 purchase price included a modern mill, 3,400 acres of timber, interest in 3 vessels and a lumberyard in San Francisco.

One of the largest sawmills on Puget Sound, Mukilteo’s Crown Lumber could produce over 200,000 board feet of lumber in a single 10-hour workday. The mill was built over a wharf where, because of its deep-water harbor, ocean-going ships could tie up and load lumber cargo. Small steam schooners could carry about 400,000 board feet in a single load; 3, 4 and 5-masted sailing ships could carry 500,000 to 1.6 million board feet, and larger, steel-hulled freighters could carry about 5 million board feet per load. In 1928, one ship was reported to have carried a record 8 million board feet.

Mukilteo’s lumber mills occupied about 20 acres of waterfront property where the new ferry terminal is now being constructed. Besides Crown Lumber, there was also the Yukon Lumber Company (aka Mukilteo Manufacturing Company) and the Mukilteo Shingle Mill. The mill operations employed about 200 persons, with work for another 30 to 60 longshoremen and many more in related fields. Common labor rates in the early 1900s were $2.00 to $2.50 per day for 10 hours work. The sawmill operated six days per week. In 1918, unions succeeded in obtaining an 8-hour workday. When the mill operations closed in 1930, the common labor rate was $3.50 per day for 8 hours work.

The lumber mills were a huge part of Mukilteo’s economy. Nearly the entire population was somehow connected either directly or indirectly to mill operations. Mill workers were paid monthly. Their families shopped in Mukilteo stores. Seasonal workers such as longshoremen or loggers stayed in Mukilteo hotels or rooming houses. They dined in Mukilteo restaurants, drank in local saloons and saw movies at the Hadenfeldt Theater. Thus, it was a major shock to the town when the Depression hit and the mills closed.

The Mukilteo Shingle Mill had been destroyed by fire in 1929, and the Crown Lumber and Yukon Lumber mills closed in 1930. Many of the mill workers (including almost all the Japanese workers) left town in search of employment elsewhere. Mukilteo nearly became a ghost town. The resilience of those that remained during the Depression is a tribute to Mukilteo’s survival. Many residents had gardens for raising vegetables, potatoes and chickens. Bartering for goods and food became commonplace. What remained of the Crown Lumber Mill was destroyed by fire in 1938.

Mukilteo’s economic downturn lasted for nearly a decade. Salvation came in the form of the U.S. Navy, which built a large ammunition facility on the former Crown Lumber property. Constructed in the early months of WW II, the facility included a barracks and massive pier, and provided jobs for about 600 workers. The property was later used by the Air Force for a fuel storage facility before becoming available for Mukilteo’s new ferry terminal. The old Navy barracks building was taken over by NOAA and will soon be replaced by a more modern facility. Although no longer a lumber town, Mukilteo’s rich history remains deeply rooted in our lumbering legacy.

Originally published in the 4/22/2020 issue of the Mukilteo Beacon.