By Joanne Mulloy, President, Mukilteo Historical Society

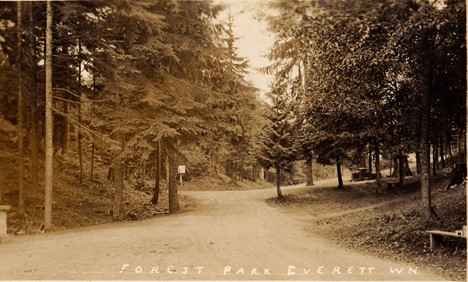

When I tell people about my memories of visiting the bears at the Forest Park Zoo. I get strange looks. When discussing it with those from this area, we name the zoo animals we remember. I have vague memories of other animals but mostly remember bears and many peacocks. Children would chase the peacocks for their feathers, but they were easily picked up from the ground and most of my friends had a bouquet of peacock feathers in their room. I spent a lot of time at Forest Park as a child: in the wading pool, at the playground and in the picnic shelter with my family. I was over the moon when I won a sleeping bag at an event sponsored by the Everett Police Department. As an unmotivated teenager, I “worked” for the Parks Department during the summer in the time of their Van Go traveling art bus. I also worked at the Animal Farm cleaning out farm stalls and putting down fresh hay. We took any unfertilized eggs home and I would use them to bake cakes. The first day I ever skipped school, I explored the trails at Pigeon Creek with a friend and will always remember that day. For these reasons, I wanted to explore the history of the park. Thank you to the Everett Walking Tour for the photos included here, and many details. The 1989 book, “The History of Everett Parks, A Century of Service and Vision” by Allan May and Dale Preboski was a valuable resource.

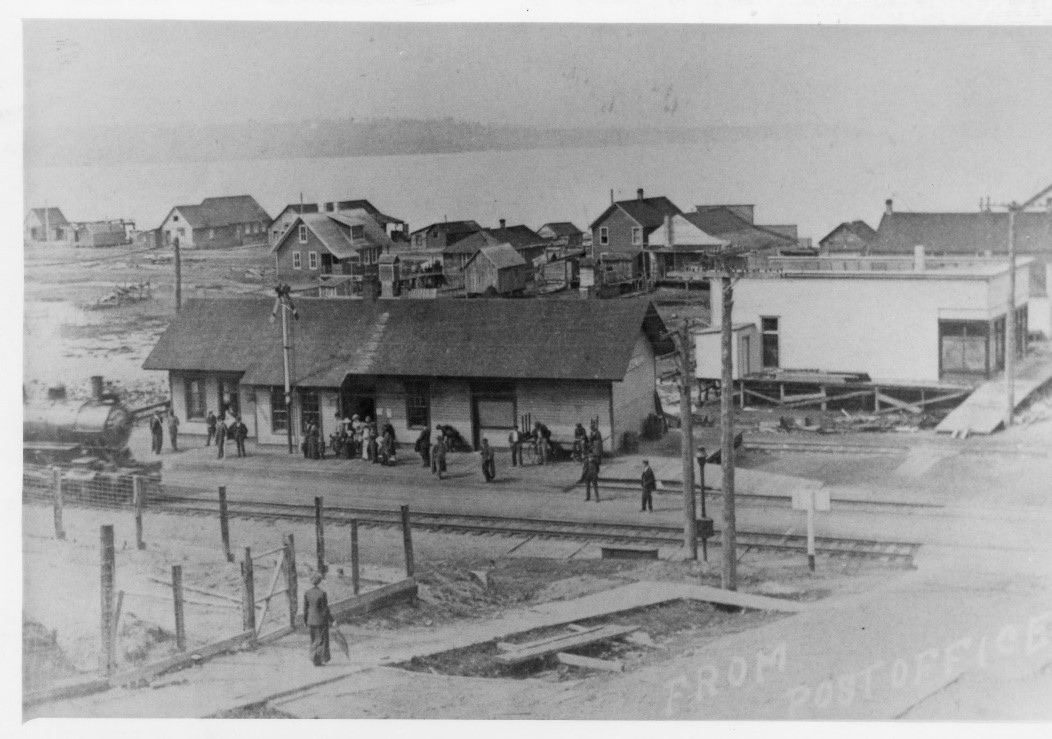

The history of Forest Park started much earlier than I expected. The first ten acres were purchased on September 27, 1894 for $4300 with the requirement that $600 in improvements be completed in the next five years. This time frame was due to just coming out of a depression. In 1907, voters approved a five-man Park Commission to be appointed by the Mayor. In 1909, eighty acres of land were purchased to expand Forest Park and in 1913, Forest Park was officially named. Before that, it was called South Park or Swalwell Park (after the family that previously owned the land).

In 1914, the City of Everett created the zoo with three deer, two coyotes, two pelicans that were given to the City by the game warden. Five years later, the Forest Park Zoo was officially established. Over the next decades, when the park was being run by Oden Hall, his brother Walter and his nephew, John, the zoo grew. With little money, Hall collected young animals from overcrowded parks along the west coast including British Columbia. He traded with circuses traveling through the area. The Halls raised food for the birds and other non-carnivore animals in their fields and arranged for farmers and highway patrols to notify them of dead livestock or roadkill. The zoo animals changed over the years. At one time during the 1920s, it was said there were 200 animals, including bison, elk, deer, zebras, an Indian elephant named Rosie, a wallaby kangaroo, 4 bears, a marmot, goats, coyotes, a badger, raccoons, rabbits and a skunk. Later there were lions, leopards, monkeys, an eagle, owls and peacocks. Alvin Weiss was appointed zookeeper in 1945. By the fifties, it had become too expensive and it was scaled back. The zookeeper position was eliminated in 1958. Three bond issues to fund the zoo were turned down by voters during the 1950s. In 1962, most of the zoo was torn down. For many years, peacocks still walked freely in the park. In 1976, the last animals, the bears, were sent to the Olympic Game Farm in Sequim.

In 1915, an emergency fund was created from the park budget, putting unemployed people to work on improvements to the park. The following year, more land was purchased to expand it. That purchase linked the park to Puget Sound through Pigeon Creek and established its permanent form. In 1919, the same year the zoo was established, $13,000 of a bond approval went towards more improvements to the zoo, playground and park. Ten years later, the area where Floral Hall, the greenhouses and the administrative offices are was acquired from the Norwegian Lutheran Church. The 1930s brought help from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for more development including plantings, terracing the hillside, building trails and clearing pastures for the zoo animals. The wading pool was built during this time. It was sponsored by the Lions Club and at 75 by 45 feet was one of the largest and best in the northwest. In the center was a statue of two larger than life babies designed by artist Frances Hedges.

Floral Hall was built by the WPA from lumber logged near Three Lakes in the National Parks rustic style. It was completed in 1940 in time for the Snohomish County Gladiolus Society’s show. Floral Hall was the home of many flower shows. A dance floor and kitchen were added in the 1960s. It originally had a 12-foot veranda on the north and west sides. The hall was renovated in 1989 and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

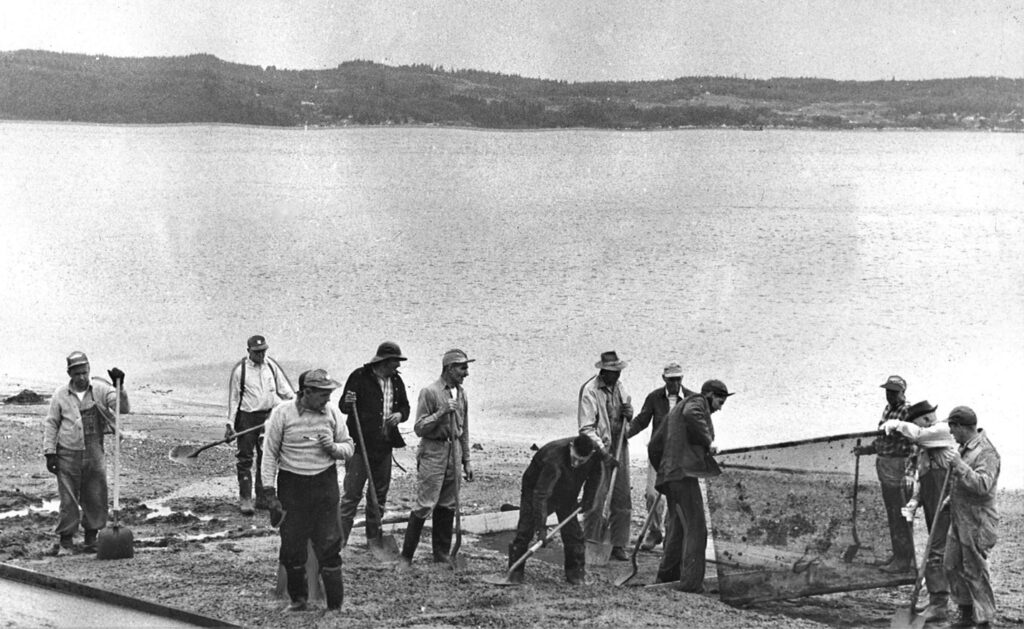

The WPA sponsored “play days” with organized games and activities. They offered swimming lessons, archery, and a weekly library book truck. In 1941, an area in lower Forest Park called Maple Heights Park was leased to the Boy Scouts who used it for seven years. Improvements were made to Pigeon Creek and Bathing Beach which opened on July 1, 1943. The Maple Heights Beach was later abandoned, and the overhead crossing was removed. When the WPA was discontinued, development faded.

In the early 1950s, the Skiers Club built a ski jump in the park for a two-day Snofair where a crowd of 7000 watched 70 contestants. A second, popular Snofair was held the following year. Due to lack of snow, the American Ice Company supplied the slipperiness. In 1963, the Everett Community College Carpentry Class built a concession building at the park and ten years later it became the Recreation Office. Two years later they built a picnic shelter on the northeast corner of the Kiddie Korral in the park. In 1967, the Everett Parks and Recreation Department moved out of City Hall and into the park office at Forest Park which was also built by the Carpentry Class.

In 1970, the Animal Farm was created at the park at the zoo’s old butcher shop location at the west end of the park. In 1975, the Swim Center opened to the public with a removeable roof that was unique at the time. The Thanksgiving Day storm of 1984 severely damaged the fabric roof and it was replaced with a permanent roof in 1985. Forest Park is currently 110 acres and a major center of the Everett Park system.

For more information:

Nostalgia tinged with sadness: The story of Forest Park Zoo

Forest Park Self-Guided Walking Tour

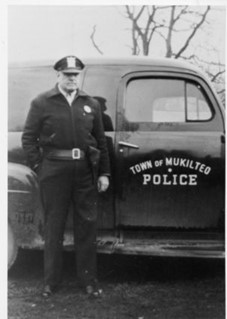

Originally published in the 9/9/2020 issue of the Mukilteo Beacon.